Hunting and Literature: When Writer-Hunters Tell of Nature, Silence, and the Ethics of the Act

Hunting and literature. Two worlds that may seem distant, yet are deeply connected. Hunting has never been merely a physical activity, but a symbolic act, a metaphor, a way to confront both nature and oneself. This truth has been understood, lived, and recounted by some of the greatest writers in the world. In this journey through pages, we rediscover the profound meaning of hunting through the eyes—and the pens—of immortal authors: from Hemingway to Rigoni Stern, from Tolstoy to Mishima.

Contents

ToggleErnest Hemingway: Hunting as a Metaphor for Life

Ernest Hemingway is probably the writer who more than any other has made hunting a central element of his vision of the world. In his stories, hunting is at the same time a physical and emotional experience, a metaphor for existence, struggle, death and dignity.

In the masterpiece “The Snows of Kilimanjaro”, for instance, the African landscape and the leopard hunt serve as both setting and symbol of the protagonist’s search for meaning, a dying writer reflecting on his life. Hemingway had a deep love for hunting—raw, wild, unfiltered—and saw it as one of the last authentic experiences available to modern man.

His “Green Hills of Africa” is a celebrated hunting diary from a 1930s expedition in Tanzania. There, among the bush and baobabs, the author reflects on the beauty of nature, the ethics of the hunter, and the spirituality of the act. For Hemingway, the rifle is a tool that demands responsibility, awareness, and a confrontation with one’s conscience. Hunting becomes a moral test.

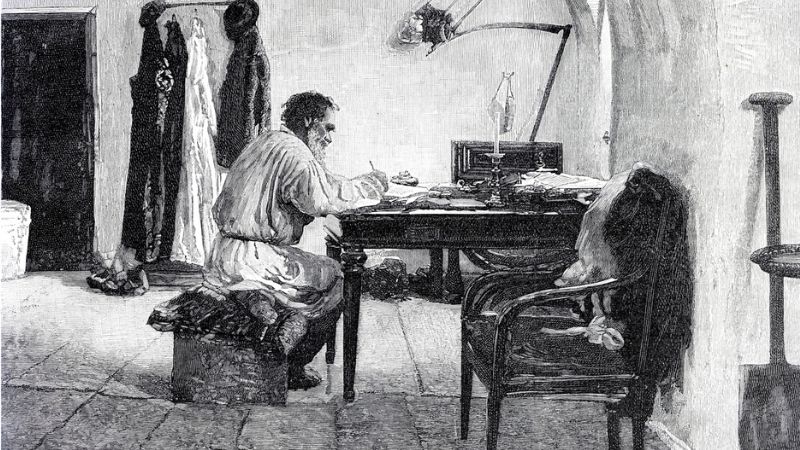

Leo Tolstoy: The Contemplative Pleasure of the Hunt

Long before Hemingway, the Russian literary giant Leo Tolstoy described hunting in his diaries and stories as a form of immersion in nature and silence. In the novella “Kholstomer” and his autobiographical writings, Tolstoy portrays winter hunts on foot or horseback through the Russian steppes not as acts of aggression, but as exercises in harmony with the landscape, in solitude, and in enduring the cold. For him, hunting was almost a meditative act—a return to truth.

Mario Rigoni Stern: The Forest as Home, Hunting as Listening

Now to Italy, and to one of the greatest literary voices of the 20th century: Mario Rigoni Stern. A soldier, writer, and hunter, Rigoni Stern turned Asiago and its surrounding mountains into a literary universe full of poetry, nostalgia, and authenticity.

In books like “Men, Woods and Bees”, “The Grouse Wood”, and “Seasons”, hunting is part of a deep, respectful relationship with the landscape, animals, the rhythm of the seasons, and memory itself. The woodcock, the capercaillie, and the chamois become sacred creatures—observed, earned, and thanked.

There is never euphoria in the shot, only awareness. No display, only gratitude. For Rigoni Stern, hunting means being worthy of the forest—entering in silence, listening, understanding. And sometimes, even walking away.

His writings are steeped in hunting ethics, love for the mountains and nature, and that philosophy of restraint that every conscious hunter should embrace today.

José Ortega y Gasset: The Hunter as Philosopher of the Instant

While Hemingway described hunting with raw narrative realism, Spanish philosopher José Ortega y Gasset offered one of the most fascinating theoretical reflections in “Meditations on Hunting”. In it, he explores the deeper dimensions of the hunting act—not as sport or pastime, but as a primal expression of man’s need to measure himself against nature.

For Ortega, hunting is a “state of creative tension”, a way to be more alert, more present, more authentic in the world. It’s also a space where man rediscovers his instinct, his limits, and his connection to animals and the environment. The hunter, for Ortega, is not a destroyer, but an active contemplator of life and death—a concept that remains a foundational principle of ethical, sustainable hunting today.

Jack London: Instinct, Survival, Wilderness

In “The Call of the Wild” and “White Fang”, Jack London narrates a return to primal nature through the eyes of animals. But in his Yukon stories—like “To Build a Fire” or “Love of Life”—hunting is necessity, struggle, survival against death. In these tales, nature is both beautiful and hostile, and hunting becomes a tragically human act: at times redemptive, at times desperate.

Yukio Mishima: Hunting and the Aesthetic of Death

Japanese writer and playwright Yukio Mishima included hunting in his works through a very particular lens: aesthetics. In “The Red Roofs” and “Confessions of a Mask”, the moment of the shot and the confrontation with the animal become epiphanies. Hunting is a theatrical scene, full of symbols. Mishima turns it into a discipline of beauty and cruelty, a mirror of the tension between Eros and Thanatos.

Karen Blixen: Hunting as Romantic Narrative

Danish author Karen Blixen, famed for “Out of Africa”, recounted her hunting experiences in Kenya with a uniquely feminine sensitivity. In her writing, hunting is part of a narrative landscape made of sunsets, animals, fragile relationships, and ethical questions. Her world teeters between colonial elegance and deep respect for African land. Her vision is lyrical and melancholic—like the Africa she depicts.

Carlo Cassola and Dino Buzzati: Hunting as Solitude and Symbol

Post-war Italian literature also addressed hunting in symbolic terms. In “The Colomber” and “The Collapse of the Baliverna”, Dino Buzzati writes of hunts that become metaphors for the unconscious and impending fate. Carlo Cassola, in lesser-known stories, describes silent, melancholic hunters lost in the Tuscan mist—more intent on finding themselves than on shooting game.

Why Read the Great Hunter-Writers Today?

In an age where hunting is often reduced to a stereotype—at best misunderstood, at worst demonized—reading these authors helps bring the conversation back to a higher plane: cultural, spiritual, human. It reminds us that hunting is not merely about killing an animal, but about entering a slower rhythm of time, reconnecting with nature, and facing silence. It is effort, waiting, ethics—and often, renunciation.

Hunting literature gives us a vision of the hunt as an act of awareness, where every gesture holds meaning, where man is not a dominator but a fragile part of the ecosystem.