There is a path in the forest, hidden among the ferns and low branches, that tells a story as old as the world. It is the path of the women hunters.

A tale of proud sovereigns, untamable goddesses, silent rebels, and Amazons swift as the wind. A story few know, but one that deserves to be heard.

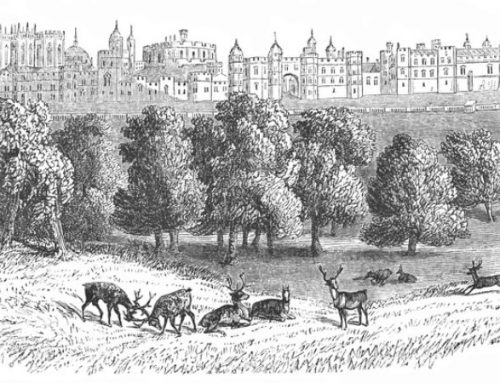

When we think of hunting in history, we almost always imagine a male-dominated world: kings and nobles, hunters with rifles or bows, packs of dogs in tow, trophies to display. But if we dig into our collective memory, through the folds of history and the margins of official records, another figure emerges: that of the woman hunter.

A figure rooted in mythology, blossoming in Renaissance courts, riding through the woods of the 19th century, and emerging—free and proud—in the 20th. A journey marked by courage, elegance, and a passion for nature. A story of freedom, defiance, and a deep connection with the wild.

The Goddesses of the Hunt: From Artemis to Diana

The journey begins long before historical records. In Greek mythology, hunting is a divine, feminine, and wild domain ruled by Artemis, goddess of the moon and the forests. With her silver bow always at the ready, surrounded by nymphs and animals, Artemis embodies absolute freedom. She knows no bounds, rejects the rules of men, protects the young and the innocent, yet does not hesitate to punish those who violate the purity of her world.

And then there are them—the writers, the artists, the travelers. Women who turned hunting into a poetic act, a declaration of identity, a bridge between culture and instinct. Not hunters out of necessity, but by choice—drawn by a love for the wild, for silence, for the delicate balance that only unspoiled landscapes can offer.

Two names shine brighter than most: Karen Blixen and Gertrude Bell. Women with vastly different styles and life paths, yet united by a shared vision: hunting as a path to freedom, a deep connection with the untamed world, and a form of personal expression.

Karen Blixen: The Voice of the Savanna

Karen Blixen, a Danish writer, lived in Kenya for nearly twenty years, from 1914 to 1931. In her most famous work, Out of Africa, she recounted with haunting sensitivity the beauty and harshness of life in the Rift Valley, on a coffee plantation at the foot of the Ngong Hills.

Beyond managing the plantation and building meaningful relationships with local communities, Blixen lived in close harmony with African nature—observing it, loving it, and—yes—hunting it. She did so alongside the man she loved for her entire life, Denys Finch Hatton, a British pilot, explorer, and hunter with a restless spirit.

But for Karen, hunting was never a mere predatory act: it was ritual, aesthetics, narrative tension—an integral part of life in the savannah. She wrote about hunting in lyrical tones, speaking of the nobility of wild animals, the precision required in every gesture, and the profound respect owed to the prey. In her words, the huntress is never arrogant: she is part of the balance, a guardian of the landscape, an enchanted observer and, when necessary, a conscious predator.

Her stories convey a sense of suspended time, typical of the great African hunts: a long, silent wait, broken only by the sounds of the wind and birds. And when the shot is fired, it is done with measure, with respect, with melancholy.

Gertrude Bell: the Desert Huntress

Far more rugged and militant was Gertrude Bell, a true pioneer of archaeology, geopolitics, and British diplomacy in the Middle East. Born in 1868 into an upper-class industrial family in England, Bell was one of the first women to graduate from Oxford. Soon after, she began traveling alone—armed with notebooks, maps, and often a hunting rifle.

She crossed the deserts of Syria, Iraq, and the Arabian Peninsula, sleeping in Bedouin tents, studying ancient ruins, and drawing maps that would later be used by the British Empire to redraw the borders of the Middle East.

In these harsh lands, where few European women dared to set foot, Gertrude earned the respect of local tribes not only through her intelligence and diplomacy but also through her skill in riding and handling weapons. She often hunted out of necessity—gazelles, birds, hares—but also to share with her hosts the ancient ritual of a meal earned by one’s own hands, a gesture that helped her be accepted as an equal.

For her, hunting was part of cultural negotiation: a way to demonstrate adaptability, strength, and knowledge of the land. Even in her diaries, there’s a palpable sense of respect for the natural world—but filtered through the gaze of a pragmatic explorer, a woman who—during the Victorian era—managed to carve out a space for herself in a world where only men were expected to speak.

She was nicknamed “the Queen of the Desert”, and her figure inspired films, novels, and essays. She was a woman who spoke Arabic, wrote letters to Winston Churchill, and moved through the dunes with the same ease with which she leafed through an ancient manuscript.

For her, hunting was part of a life of action, discovery, and total immersion in an “other” world—one to be understood and respected. A direct bond with a vast and indifferent landscape, where survival meant adapting, observing, and moving with precision. Exactly as every good hunter does.

Two Faces, One Same Freedom

Blixen and Bell. Two profoundly different women—one a poet of the landscape, the other an explorer of the unknown—yet united by an intimate and personal vision of hunting. Not a spectacle, nor a trophy, but a gesture of immersion, of silence, of connection with the land and with themselves.

Their stories offer us a feminine dimension of hunting, made of intelligence, balance, beauty, and strength. And they remind us that every woman hunter carries within her an ancient legacy—one that today can be rediscovered and told without fear, with respect and admiration.

Today: A Legacy That Still Walks the Woods

Today, the presence of women in the hunting world is steadily growing. Women who are no longer content to remain spectators, but live the forest, the dog, the plains, and the mountains with the same intensity, care, and respect as men. Women who know the language of the wild, who follow tracks with patience, who engage with nature without needing to ask for permission.

Women who are rediscovering a primordial bond—between body, breath, landscape, and instinct. Because hunting, when lived with awareness, is also this: a practice of deep listening, a form of presence, a test of freedom.

Conclusion: Telling the Hidden Story

The path of women who hunt has long been obscured by the leaves of prejudice, but now it is becoming visible once again. It is a story made of goddesses and queens, rebels and amazons, rifles and silences. A story to be told, honored, and passed down.

Because, in the heart of the forest, femininity and the wild meet, and together they write one of the most fascinating chapters in the history of hunting.