By the end of the 19th century, Africa was a continent shrouded in mystery and legend. For bourgeois and colonial Europe, it represented the “land of beginnings,” an untouched space where nature still spoke with a primordial voice. It was the absolute elsewhere—unreachable and irresistible.

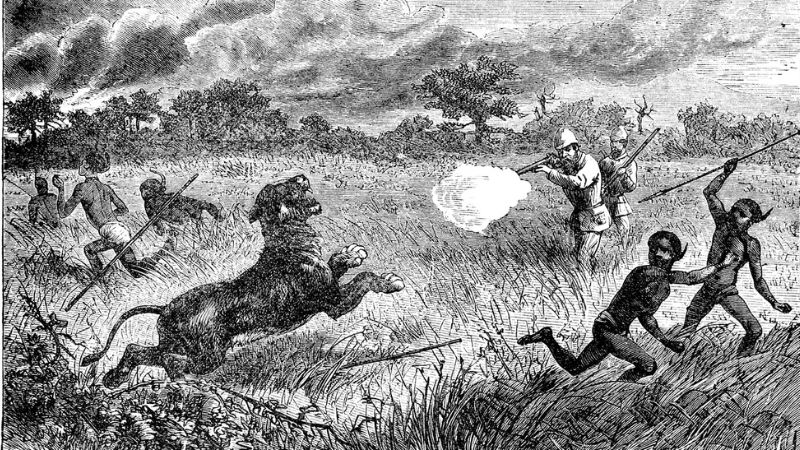

The Dark Continent drew explorers, botanists, soldiers, missionaries, and, of course, hunters. Men in search of glory, trophies, knowledge—or, often, mere adventure. Africa was the ideal canvas upon which to project epic dreams, romantic fantasies, and personal obsessions. It was also a harsh, unforgiving land that tested both body and spirit—and often did not forgive.

The wild allure of late 19th-century Africa was inextricably tied to the figure of the white hunter: hero, anti-hero, storyteller, and explorer. Some of these men became legends—protagonists of books, tales, and chronicles. Their stories, even today, retain a mythical aura, yet cast a long shadow: that of ivory hunting, animal massacres, and colonial domination.

In this journey through the savannas, rivers, and forests of a bygone Africa, we will discover who the great hunters of that century were, what they sought, and what they left behind.

The Age of White Gold: The Ivory Industry Between Domination and Destruction

By the end of the 19th century, ivory was one of the world’s most prized commodities. Known as “white gold,” it was used to produce luxury goods, handles, billiard balls, sculptures, piano keys, combs, and ornamental decorations. Demand was immense, fueled by European and American markets, and Africa became the epicenter of extraction.

This demand transformed hunting from a sporting activity into a systematic industry. Entire expeditions were organized with the sole purpose of finding and killing elephants for their tusks. Ivory caravans, guarded by armed mercenaries, moved from collection points toward the eastern and western coasts, from where the cargo would depart through ports like Zanzibar, Mombasa, Luanda, or Dakar.

The impact was devastating—ecologically, socially, and politically. Thousands of elephants were slaughtered every year, pushing entire local populations to the brink of collapse. African beaters were often reduced to semi-slavery, paid a pittance and exploited to exhaustion. The ivory routes also became routes of human trafficking: slaves and tusks traveled side by side, bearing witness to the brutality of that trade.

Politically, the ivory trade became one of the driving forces of colonial expansion. Large European companies, in collaboration with governments and military authorities, used hunting as a pretext to seize land and resources. The penetration into the African interior was often led by hunters, explorers, and ivory traders—the first to venture where no European had ever been.

While a few, such as Selous or Baker, showed some awareness of the issue, most acted without restraint, driven by profit and glory. It was only in the early decades of the 20th century, with the first conservation policies, that people began to grasp the scale of the disaster. But by then, the damage had been done: in many parts of Africa, the trumpeting of elephants vanished forever.

The Dark Side: The Ivory Hunt

While some hunters acted out of passion or for science, many others were tools or key players in the ivory trade. By the end of the 19th century, elephant tusks were highly sought after in Europe and America—for piano keys, knife handles, and ornaments. Prices rose, and the rifles fired.

Thousands of elephants were exterminated. Entire herds disappeared within just a few seasons. Contemporary accounts, when read with a discerning eye, speak of journeys undertaken solely to find new “herds to work.” Hunting turned into extermination—into industry, into plunder.

Even legendary figures like Selous took part in this activity, albeit with different limits and sensibilities. Only at the beginning of the 20th century did the first forms of protection begin to appear—often initiated by the very hunters who had converted to conservation.

Frederick Courteney Selous: The Gentleman Hunter

Selous is perhaps the most famous of the African hunters of the Victorian era. An Englishman—elegant, educated, and athletic—he was a naturalist as well as an exceptional marksman. He began hunting in Africa in 1871, and for over twenty years explored the regions between the Limpopo and Zambezi rivers.

He authored numerous books—including A Hunter’s Wanderings in Africa—in which he vividly recounted his encounters with lions, elephants, buffalo, and rhinos. He was admired by Theodore Roosevelt, who considered him a model of the ethical and sporting hunter.

Selous died in 1917 during the First World War, in Mozambique, struck by enemy fire while serving as an officer. His name lives on in the great Selous Game Reserve in Tanzania.

Curiosity: It is said that Selous could track an animal for miles without ever losing its trail. He was known for his respect toward animals and his deep knowledge of local tribes.

William Cotton Oswell: The Hunter Alongside the Explorers

A doctor, adventurer, and naturalist, Oswell is remembered for his expeditions in the Kalahari alongside David Livingstone. He was an excellent hunter, but also a man of strict ethics. He hunted out of necessity and for study, never out of vanity.

He took part in the discovery of the Zambezi River and the lakes region of southern Africa. He was among the first Europeans to hunt elephants in the Kalahari, but his journal is also full of reflections on restraint and respect.

Anecdote: During an expedition, Oswell refrained from shooting an elephant when he noticed it was a mother with a newly born calf. This gesture was greatly appreciated by the local guides, who nicknamed him “big heart.”

Henry Morton Stanley: The Double Face of the Expedition

Famous for having found Livingstone (“Dr. Livingstone, I presume?”), Stanley was also a hunter and man of action. His expeditions in the Congo and along the Lualaba River were marked by clashes, sacrifices, and violence. He was ruthless, determined, and saw hunting as a form of supremacy.

His chronicles describe the killing of elephants, hippos, and large felines in an epic tone. But today, we know that many of his actions were an integral part of the Belgian colonial project, which was often disastrous for the environment and local populations.

Historical Note: Stanley was one of the key figures in opening central Africa to the West, but also one of the symbols of the moral ambiguity of that period. His figure remains controversial.

Roualeyn Gordon-Cumming: The Lion of the Pen

Scottish, military by training, and a passionate hunter, Roualeyn Gordon-Cumming was one of the first Europeans to describe hunting in southern Africa in detail. Between 1843 and 1845, he traveled in areas now part of South Africa, Botswana, and Zimbabwe, hunting elephants, lions, and rhinoceroses.

His book, Five Years of a Hunter’s Life in the Far Interior of South Africa, became a bestseller in England, thanks to its epic and adventurous style. His descriptions are vivid, and his hunting tales – especially those of lion hunts – became legendary.

Anecdote: Nicknamed “the living lion” for the courage he showed during a night attack in which he killed two lions just a few meters from his tent, he was celebrated in London salons as a romantic hero, although his actions were not without criticism for their cruelty.

Samuel White Baker: Hunter, Explorer, and Defender of Wildlife

Sir Samuel Baker was one of the first Europeans to explore the Upper Nile and discover Lake Albert. He was also great hunter, known for

His most famous book, The Nile Tributaries of Abyssinia, recounts incredible adventures, as well as naturalistic and anthropological observations.

Curiosity: Despite the intensity of his hunts, Baker was one of the first to denounce the decimation of elephants due to the ivory trade. Married to Florence, a courageous woman who accompanied him on his expeditions, they formed one of the first “safari couples” in history.

Charles Baldwin: The King of Elephants

Little known to the general public but legendary among African hunters, Charles Baldwin is remembered as one of the most prolific “elephant hunters” of the second half of the 19th century.

It is said that he killed over 1,000 elephants throughout his life, mostly in the area now known as Zimbabwe. His feats are noted for their cold-bloodedness, audacity, and deadly accuracy with his two-pound rifle.

Historical note: His deeds, passed down orally and through letters published in English magazines, inspired many young adventurers of the time. However, his name is also linked to the fierce expansion of the ivory trade in southern Africa.

In addition to the well-known names, many other protagonists – often forgotten – contributed to the pages of African hunting: indigenous guides, beaters, and porters. Their knowledge of the land was extraordinary: they could read a track in the sand, recognize the alarm calls of a monkey, and sense the arrival of a predator. These men were the true architects of the success of many expeditions, yet their names were rarely remembered in books.

The interaction between European hunters and local tribes was complex: it moved between mutual respect and colonial imposition. Some hunters, like Selous and Oswell, sought dialogue, learned the languages, and adopted customs. Others used force, exploiting and sometimes harshly suppressing the indigenous populations. Exploring this relationship allows us to understand hunting not only as a technical act but as a meeting (or clash) between cultures.

Where hunting took place: the geography of legendary hunting

The places of great African hunting were often remote areas, on the border between savanna and forest, between desert and river. The most hunted areas in the 19th century were:

-

The Limpopo and Zambezi basins (now Zimbabwe, Zambia, Botswana): the kingdom of elephants and buffalo.

-

The Upper Nile region (Sudan, Uganda): explored by Baker, rich in hippopotamuses, crocodiles, and antelopes.

-

The Kalahari and Bechuanaland (now Botswana): deserts and savannas dotted with waterholes, the stage of Oswell’s expeditions.

-

The Rift Valley and the Great Lakes (Kenya and Tanzania): crossroads of lions, rhinoceroses, and migratory herds.

The aesthetics of the hunter: trunks, double rifles, and trophies

The 19th-century hunter was also an aesthetic symbol. He wore colonial canvas outfits, tall boots, and belts with brass cartridges. He traveled with leather trunks, folding tents, silverware, books, and dream rifles.

Weapons were true works of art: Holland & Holland double express rifles, two-pound Express rifles, finely engraved percussion rifles. The camps were small worlds: with kitchen tents, writing tables, folding armchairs, and carpets.

Trophies were displayed in European drawing rooms but also used as currency to obtain favors or contracts. The obsessive collecting of tusks and horns often intertwined with a narcissistic dimension: the hunter as a dominator, as a collector of power.

Between Myth and Awareness

The great African hunters of the 19th century appear to us today as complex figures. They were adventurers, explorers, naturalists, and writers. Some were pioneers of conservation, while others were protagonists of a destructive economy. Their stories still fascinate us because they tell of an immense and wild Africa, of men standing alone before a lion, of campfires under the stars, and of endless silences.

But reading their exploits today also means reflecting. Understanding the impact of our actions, the fragility of nature, the value of memory, and responsibility.

Because the true hunter, today as then, is not the one who kills the most. It is the one who knows how to look at an animal and, in that moment, feel the beauty of the entire world.