The President Among Lions: When Africa Became the Stage of Power

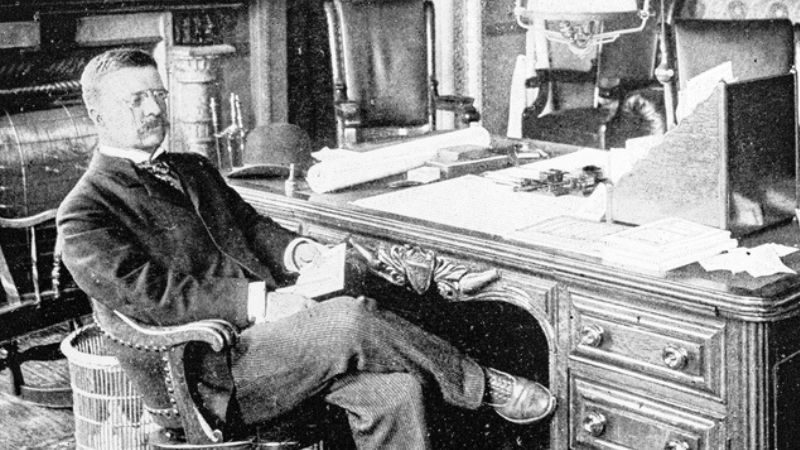

In 1909, just a few months after finishing his presidential term, Theodore Roosevelt set sail with his son Kermit for British East Africa. It was not a pleasure trip, nor merely a scientific expedition: it was an epic undertaking — a bold statement of style, power, and American civilization. The Roosevelt African Safari is still considered the most famous hunting expedition in the history of the African continent.

Somewhere Between Myth and Chronicle, the expedition combined science, politics, muscle-flexing, and a genuine passion for nature. Roosevelt was a self-taught naturalist, an avid hunter, a man who saw outdoor life as the ultimate expression of masculinity and American identity.

A Colossal Undertaking

Organized with the support of the Smithsonian Institution and the American Museum of Natural History, Roosevelt’s safari had an official purpose: to collect specimens for enriching the scientific collections of the United States. But it was also a grand display of prestige — the presence of the former president drew worldwide attention.

The expedition lasted nearly a year. It began in Mombasa (now Kenya), crossed through Uganda, Lake Victoria, and the Nile region, all the way to Khartoum in Sudan.

Record-Breaking Numbers

During the safari, more than 11,000 specimens were collected, including:

512 large game animals

Elephants, lions, buffalo, rhinos, hippos, zebras, giraffes

Hundreds of birds, reptiles, and insects

Theodore Roosevelt alone killed:

-

11 elephants

-

17 lions

-

7 leopards

-

Over 20 Cape buffalo

His son Kermit was no less impressive, demonstrating skill and composure. Every animal taken was treated with scientific rigor: skinned, cataloged, and taxidermied.

The Safari Route: Stops, Encounters, and Landscapes

Roosevelt’s African journey began in April 1909 and ended in March 1910. It was an epic itinerary that crossed some of the wildest and most spectacular areas of East Africa. Here’s a detailed description of the main stages of the safari:

1. Mombasa (Kenya): The journey began at the port of Mombasa, where Roosevelt and Kermit landed after crossing the ocean. From there, they boarded the Uganda Railway, one of the hallmark infrastructures of British imperialism in Africa.

2. Nairobi and the Athi Plains: At the time, Nairobi was a small railway station but already a hub of British colonial life. The Roosevelts set up their first camps here. In the Athi Plains, with their tall grasses and rolling savannas, the first hunts began — targeting antelopes, zebras, and warthogs. Roosevelt noted the wild beauty of the land, comparing it to a primeval Eden.

3. Rift Valley and Lake Naivasha: From Nairobi, they moved on to the Rift Valley, passing the shores of Lake Naivasha. It was in these areas that they hunted their first buffalo and hyenas. Roosevelt fell in love with the lake’s rich birdlife, and many bird specimens were collected for the American Museum of Natural History.

4. Mount Kenya and Aberdare Regions: Here began the true encounters with the “Big Five.” The mountainous terrain and dense forests were home to lions, rhinos, and elephants. Roosevelt shot a massive black rhino that suddenly charged his horse, narrowly saving himself with a well-placed shot just in time.

5. Lake Victoria Region: Traversed by canoe and dugout, the Lake Victoria area was the scene of hippo and crocodile hunts. Roosevelt recounts a memorable incident in which a wounded hippo capsized a supply-laden boat, forcing the entire camp to survive on reduced rations for days.

6. Uganda and the Nile River: The journey continued north along the White Nile. Here, Roosevelt killed his largest elephant — a lone bull with tusks over two meters long. Local legends spoke of the elephant as a “spirit of the forest” — an animal no one dared to hunt for fear of a curse.

7. Southern Sudan and Khartoum: The final leg of the expedition. In Khartoum, they boarded a ship back to Europe. This stage was less about hunting and more diplomatic: Roosevelt met with British officials and inspected the administrative system of the Anglo-Egyptian Sudan.

Safari Tales and Legends

The Sunset Lion: During a hunt near the Guaso Nyiro River, a lion emerged from the bush just as the sun was setting. Caught by surprise, Roosevelt faced it on foot and brought it down with two rapid shots. Kermit later wrote it was the moment he saw his father “both happiest and fiercest at once.”

The Lone Elephant of the Nile: Local lore told of an old bull elephant that roamed alone along the Nile’s banks, appearing only at dawn. Roosevelt managed to track and kill it after a three-day stalk. Its tusks became some of the most prized specimens sent to the Smithsonian.

The Rhino Charge: On one occasion, a black rhinoceros charged Roosevelt at close range. His horse panicked, and only a precise shot to the animal’s skull saved him. In his memoirs, Roosevelt wrote: “I felt damnably alive… as if I were challenging the laws of the jungle face to face.”

Kermit and the Night Leopard: Kermit shot a leopard in the dead of night after tracking its footprints around the camp. The guide called it “the courage of a young lion,” and from that day, the porters began calling him Simba Dogo — the little lion.

The abundance of anecdotes, combined with meticulous scientific documentation and the extraordinary media impact of the expedition, turned this safari into an immortal legend in the history of hunting and exploration.

Hunting as Identity

For Roosevelt, hunting was far more than a passion — it was a rite of passage, a formative experience. Having grown up with health problems, he built his physical and moral strength through contact with the wild. In Africa, he sought to confront the “noblest beasts” — the so-called Big Five — following an ethical code that, for the time, was considered sporting: respect for the prey, precise shooting, and no unnecessary cruelty.

And yet, the numbers speak for themselves: the expedition was also a massive operation of wildlife extraction. Today, we look at that undertaking with different eyes, recognizing its documentary value but also acknowledging its devastating impact on some local ecosystems.

African Game Trails: The Book of the Legend

In 1910, Roosevelt published African Game Trails, a monumental work in which he chronicled the entire safari. The book remains one of the most vivid, fascinating, and controversial accounts in the history of big-game hunting.

Written in a gripping style, the work blends:

-

adventure storytelling,

-

naturalistic observations,

-

personal philosophy,

-

reflections on the meaning of hunting and conservation.

Paradoxically, Roosevelt was also one of the earliest major advocates for environmental conservation. He founded national parks, established wildlife reserves, and was a forerunner of modern ecological thinking — all while continuing to hunt until the end of his life.

Legacy and Reflection

Today, the Roosevelt Safari divides opinion. On one hand, it was an extraordinary feat in terms of logistics, scientific contribution, and storytelling. On the other, it also stands as a symbol of an era when white Western dominance extended to the subjugation of nature itself.

But its epic allure is impossible to ignore: the camps at the foot of Kilimanjaro, the white canvas tents, the long columns of porters, the glint of rifles at dawn, the journals written by kerosene lantern under the star-filled African sky.

The Roosevelt Safari remains—both for better and for worse—the ultimate icon of African colonial hunting.

A journey into the soul of man, into the heart of the savannah, and into the complexities of an era that still challenges our understanding today.

Further Reading

-

Theodore Roosevelt – African Game Trails

-

Douglas Brinkley – The Wilderness Warrior: Theodore Roosevelt and the Crusade for America

-

Edward Rice – Captain Sir Richard Francis Burton: The Secret Agent Who Made the Pilgrimage to Mecca (for comparisons with other explorers of the time)

- T. H. Watkins – The Hungry Years: A Narrative History of the Great Depression in America

(For understanding Roosevelt’s political figure in relation to his hunting legacy)

A journey through time, a hunt for the deeper meaning of adventure,a story best read with the sound of the African wind in your ears.