There was a time when Africa was a blank map, a mystery, an enchantment. A time when caravans got lost among the baobabs and the silence of the savannas, and rivers flowed nameless on English maps.

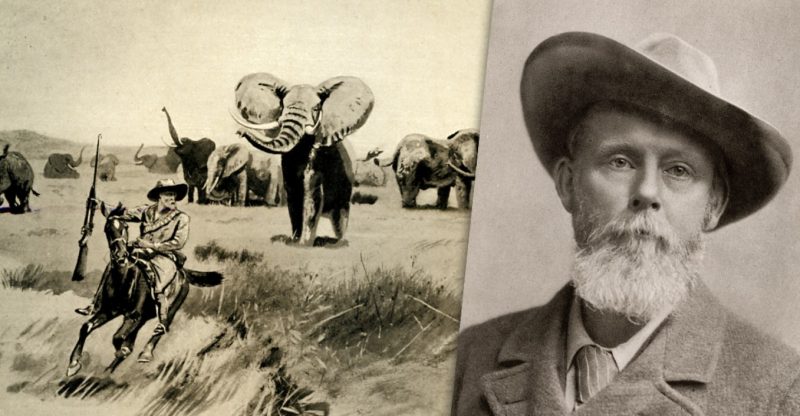

In that time—one of dreams, conquest, and danger—a lone man walked, a rifle on his shoulder and a notebook in his heart: Frederick Courteney Selous.

Born in 1851 in London, Frederick Courteney Selous was not just a hunter. He was a tireless explorer, a passionate naturalist, a valiant soldier, and a sensitive storyteller. But above all, he was a man willing to leave behind the comforts of Victorian life to embrace the grand uncertainty of the wild African landscape.

He was among the few Europeans of his time to understand that the true wealth of the continent was not merely in trophies or ivory but in the living spirit of its lands, in the silence charged with presence, in the primordial heartbeat of the savanna. Where others saw lands to conquer, he saw horizons to respect.

Selous walked lightly, observed everything, and took notes relentlessly. Not just elephant tracks or lion trails, but tribal rhythms, oral traditions, and sunsets that seemed like the songs of the gods. He could lose himself in the bush for weeks, with no longing for the civilized world, returning each time wilder, freer, more human.

It was this unique ability—to turn every step into memory and every encounter into a story—that made him immortal. His words, etched onto pages that still carry the scent of red earth and sun-kissed skin, bring us an Africa that is alive and pulsating, far from colonial caricatures and close to the breath of nature.

Matabeleland 1871–1882: The Expedition That Made Him Immortal.

He was only 21 years old when, in 1871, Selous set off for southern Africa, determined to live “like the free and wild men of the frontier.” Thus began one of the most extraordinary hunting and exploratory expeditions in history—a decade of unknown rivers, warrior tribes, storms, and pursuits in the land now known as Zimbabwe.

The Journey

- Expedition Start: South of the Limpopo, near the Tati River

- Kingdom of the Matabele: Granted hunting permission by King Lobengula

- Mashonaland & Zambezi: Untouched lands teeming with wildlife

- Hwange & Zambezi Escarpment: Home to legendary numbers of elephants, buffaloes, and rhinos

The Hunt and the Ivory Trade

The African elephant was the expedition’s undisputed protagonist, hunted not only for sport but for the “white gold”—ivory. Selous became one of the most renowned elephant hunters of his time, but he always practiced hunting with a spirit of sportsmanship and scientific observation.

“I have never enjoyed hunting for destruction. The true satisfaction lies in the challenge against the intelligence and strength of the prey.”

— F.C. Selous, A Hunter’s Wanderings in Africa

Lions, Buffalo, and Nameless Rivers

Selous faced every type of African prey:

- Lions: He hunted many, but always with respect. He wrote of a night when three lions surrounded his tent, drawn by the scent of meat. He did not fire. He remained still. At dawn, the lions were gone.

- Cape Buffalo: Described as “the most unpredictable creatures in Africa.” One charged and wounded Selous’s horse; he saved himself by climbing onto a termite mound.

- Crocodiles and Hippos: Along the Zambezi, he spent days hunting from lightweight canoes, constantly at risk of capsizing.

Selous was no conqueror—he was a cultural mediator. He lived closely with the Matabele and Shona, learning their languages, customs, and traditions. He was received multiple times by King Lobengula, who called him “the white man with the black heart,” meaning an African heart.

He knew the trails like an elephant, read the land like a hound. He used to say that before shooting, one must “learn to walk as a guest.”

Legendary Anecdotes

The White Elephant of Matopos

Among the granite hills of Matopos, the Matabele elders spoke of an old “white” elephant, whose skin, aged and dust-covered, reflected light like silver. They called him Isilwane Esilivula—“the one who disappears with the wind.”

Selous tracked it for three days through rocky valleys and mopane forests. When he finally saw it, standing alone among the boulders at sunset, he was mesmerized:

“It looked like a spirit in ivory flesh,” he wrote.

Instead of raising his rifle, he sat in silence. The old elephant lifted its trunk, looked at him for an eternity… then vanished into the trees. Selous never saw it again, but that day made him a legend.

The Buffalo on the Termite Mound

In the Lower Zambezi, Selous pursued a group of Cape buffalo. One, wounded, broke away from the herd and hid in dense underbrush. When Selous approached, the animal charged suddenly. His horse reared, and he fell.

With calm precision, he rolled behind a termite mound and, with the buffalo’s breath just meters away, fired a single shot to its neck. Sweaty, covered in mud, and out of breath, he later wrote:

“Nothing forces you to be present like the buffalo. It is death staring into your eyes, and you must decide whether to look away.”

The Night Leopard of the Tuli River

Camped on the Tuli River, Selous woke in the middle of the night to a soft sound—a breath among the leaves.

He stepped out of his tent without a lantern. The sky was strewn with stars. A few steps away, he saw the elegant shape of a leopard perched on a branch above his tent, watching but not hunting. The two stared at each other for long seconds.

Selous took a step back and murmured:

“Not tonight, brother.”

The leopard gracefully descended and disappeared into the bush. From that day on, his porters called him Ngwenya Wemphilo—“the one who speaks to leopards.”

The Bones of the Tati River

Traveling alone between the Limpopo and Tati rivers, Selous found a small pile of stones. Digging, he uncovered human remains—skulls, bones, fragments of leather satchels.

They were likely the remains of a lost Portuguese caravan from years before. No one had ever returned to tell what had happened. Moved, Selous arranged a simple burial, carved a cross into a stone, and marked the spot on his map.

“Even those who came seeking ivory deserve someone to remember their names.”

The Five-Meter Shot

One of the most famous stories—confirmed by Selous in his journals—involved an elephant cow encountered in dense dry woodland near modern-day Gweru. On foot, he was suddenly charged. There was no time to aim; he fired instinctively from less than five meters, hitting the skull with surgical precision.

“The world fell silent, then exhaled. My heart pounded like a war drum.”

The Wounded Lion Encounter

In southern Mashonaland, he tracked a lion wounded by another hunter weeks before. The animal limped, seemingly aware of the trap the savanna had set for it. After hours of tracking, Selous found it resting beneath an acacia tree.

He could have shot. He did not.

“It had the pride of a king who had lost his throne. I granted it its final night in peace. Respect, after all, is the true prize of a hunter.”

The Geography of Adventure

Selous’s journey crossed some of Africa’s wildest territories:

-

Matabeleland: Land of warriors, red rivers, and immense herds

-

Zambezi River: River hunting, quicksand, crocodiles

-

Mashonaland: Rich in wildlife and gold mines

-

Hwange: Now a national park, then a royal hunting ground

-

Limpopo Region: Abundant with lions and leopards

-

Victoria Falls: Reached on foot after weeks of marching

The Gentleman Hunter

Selous dressed like a European, wrote like a novelist, and hunted like a silent predator. He did not boast about trophies—he described landscapes. He preferred maps over medals.

In England, he became a hero. In Africa, he remained a legend. He did not colonize—he explored. He did not flaunt—he told stories. He was the inspiration for Allan Quatermain, the Victorian-era Indiana Jones.

Recommended Reading:

-

A Hunter’s Wanderings in Africa – Frederick Courteney Selous

-

Travel and Adventure in South-East Africa – F.C. Selous

-

Sunshine and Storm in Rhodesia – F.C. Selous

-

White Hunters: The Golden Age of African Safaris – Brian Herne

-

African Adventurer’s Guide – Peter Hathaway Capstick

Legacy

Selous died in combat in 1917 during World War I, at the age of 64. He was buried in Beho Beho, Tanzania, now part of the Selous Game Reserve, which bears his name and is one of the largest wildlife reserves in the world.

Today, those who walk through his old campsite may still find traces—perhaps a rusted bullet, perhaps the faint imprint of a tent. But certainly, the memory of an era when the savanna spoke only to those who knew how to listen.

“In that boundless land, where the night carries the scent of acacias and the wind whispers like an ancient drum, I was free.”

— F.C. Selous